Non-fiction Books

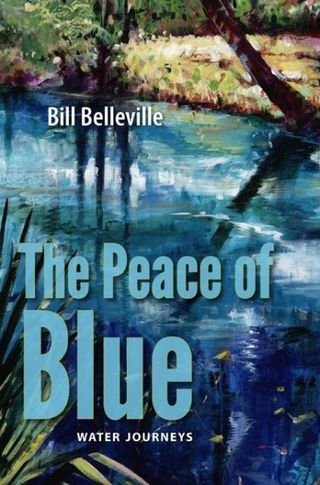

My most recent book is a collection of first person stories that all take place around water---near it, atop it, under it. An introduction explains the essential role of water in our lives---as well as our primal connection to it.

"SALVAGING THE REAL FLORIDA: LOST & FOUND IN THE STATE OF DREAMS" (A Collection of Experiential Nature Essays from Throughout Florida)

EXCERPT OF ESSAY: "Fire, Water, Friendship in the Night" on the Mosquito Lagoon of Florida's East coast

We launch in a shallow Florida cove just before sunset, excited with the possibility of having fire rise from the water.

Clumps of turtle grass float at the surface, and black mangroves hug the shore, their characteristic air roots poking up under the bushes like black pencils. My friend Bobby is in a single canoe and the rest of us—Michelle, her daughter Alex, and a few more are in kayaks.

We scuttle about until everyone is ready and then we paddle out into the Haulover, an old canal that links the Mosquito Lagoon to the north with the Indian River to the south. Long legged herons and egrets hunt near the black mangroves, each a study in precision.

The fire in the water we are hunting is bioluminescence, less of a burn than a dazzle of cold blue-green light. Although this happens in the night seas worldwide, it’s more realized in some places than others. In Puerto Rico, Phosphorescent Bay is named for the phenomenon. In the Galapagos, I've dived into Tagus Cove late at night and the bio-light there consumed me, exploding with each exhalation. On the beaches of the Outer Banks of North Carolina, I've seen puddles of it abandoned on the sand by the ebb of tide. I guess it’s been taking place in this particular lagoon for thousands of years, but we’ve only recently caught on.

Guides will take people to such places, but I usually like to go it alone, or with a few good friends. The risks may be a bit greater, but the surprises always seem somehow more real. I paddle out into the deeper canal and the surface around me becomes suspiciously flat, as if something immense is moving just below. My little boat wobbles gently. Within seconds, the back of a manatee materializes a few feet away, its gray, barnacled body like a gigantic sausage.

A shaggy snout gently breaks the water, human-like eyes deeply set, each inside a starburst of wrinkles. It glances at me, inhales. From inside its massive body, the air resonates as if in a cave. Then it sinks back down. I look over at Michelle, smiling broadly, without guile.

Despite its size, the coming and going of such an animal was incredibly delicate, almost like a disassembling of molecules. It could have flipped me in a heartbeat if it had wanted. I am exhilarated, and also deeply thankful I am still upright.

We paddle north where the canal meets the Mosquito Lagoon. It is twilight and the primitive landscape is golden. Men are fishing and drinking beer on the shore, many of them fried after hours of it. A really bad country music song celebrating the glories of "redneck women" blares from a pick-up truck. There is a small mangrove island offshore and we paddle towards it, riding a gentle evening breeze. As we go, the gray dorsals of a pod of bottlenose dolphins slice through the water nearby.

The sun vanishes and a dark cloud bank on the horizon begins to shoot out jagged spires of lightening, soundlessly. I look back to the land, now a half mile away, and see most of the fishermen packing to leave. The music shuts off and what remains is the slosh of our hulls, the cry of wading birds, the muffled sighs of anticipation.

The lagoon is encircled by public land; like the manatee, it’s a relic of what used to be. The landscape here was protected decades ago when the government bought a massive swatch of coastline to buffer its rocket launching at the Kennedy Space Center. In a strange twist, the ambitions of the future have preserved the past. Bobby, a cardiologist by day, sometimes brings his flats boat here to fish for sea trout and reds that school over the sea grasses and sandy shoals of the shallow, clear lagoon.

The cold light remains hidden and I find myself wondering if it will actually turn on tonight at all. We have brought Cyclamen sticks and we individually snap the plastic tubes to make them glow and hang them around our necks to keep track of each other. This seems a simple task, but I botch it and, for the moment, the lanyard tightens on my forehead, the glow-stick hanging against my nose, and I can't help but smile. A few of the others laugh good-naturedly at this. These are people who cherish the immediacy and enchantment of this moment, and I am glad to be here with them.

We float in the lagoon, letting the gentle evening breeze push us. It is almost completely dark now. We are all silhouettes with light sticks, finer details lost to the night. Suddenly I hear Alex’s voice from somewhere nearby, as if announcing the arrival of a special guest, one syllable at a time: “It’s hap-pen-ing.”

I look over to where I know Michelle to be. As she moves her paddle through the water, it glows dim with turquoise and she lets out a long, low woooow. I turn in my seat, watching as my own blade draws up the cold light. I hear murmurs rise around me, voices slightly higher and full of wonder, and I realize everyone is doing a version of the same thing, creating light from water. The alchemy has taken time to cook, but now it has us in its grip.

We paddle back toward the canal, where marine life is more concentrated. The lagoon water under us is so clear we can see through it, can watch as the grasses on the bottom glow with the light. Small fish and then larger ones, down deep, are outlined in blue-green.

Once we are in the canal, sunken logs on the bottom effervesce with color. Suddenly, the form of a massive alligator swims under us, odd, tiny arms from its body swishing the blue. It’s amazingly graceful, and, like the wading birds, its movements are precise.

Crabs drift along, glowing, sometimes bumping into my hull, hard calcium shells clanking oddly against plastic. Alex cups her hand in the water, and the liquid she holds sparkles as if electrified. In the distance, a dolphin arches out of the water, bringing a massive column of light with it.

I know, intellectually, that tiny, single-celled plankton called dinoflagellates do this, absorbing energy from the sun and releasing it to confuse predators at night, twisting and turning in the water. But that doesn’t explain the full magic of it to my senses. Another cove splays from the canal and we paddle into it. It is shallow and populated with great schools of mullet. When Bobby and others move far ahead they spook the mullet and the fish begin to leap from the water in great explosions of energy, like low-level skyrockets. Sometimes, in their jumps they whack into our boats; sometimes, into us. I look down, see a blue-green stingray move next to my hull, its wings undulating as if it is flying in the water.

Above, stars have filled the void over the cloud banks, and now a meteor traces a line through them. A collective murmur rises at once from us, an exhalation of natural awe. It seems as if the sky has split in two, no clear line left any more between it and the water around us. And now we have stopped being writers and doctors and whatever else we are and have become kids, alive only for this moment, in this place

.

I drift some more and it vaguely occurs to me that stardust started it all, showering this earth with its energy so long ago, and now, many molecules later, here we are in a dark Florida lagoon, watching it happen all over again. Like the dinoflagellates, we twist and turn in the night, glowing blue-green ourselves, a theater of creation in the mangroves.

We are all quiet now, and, soaked with the energy of the stars, as fully conversant as we will ever be.

Clumps of turtle grass float at the surface, and black mangroves hug the shore, their characteristic air roots poking up under the bushes like black pencils. My friend Bobby is in a single canoe and the rest of us—Michelle, her daughter Alex, and a few more are in kayaks.

We scuttle about until everyone is ready and then we paddle out into the Haulover, an old canal that links the Mosquito Lagoon to the north with the Indian River to the south. Long legged herons and egrets hunt near the black mangroves, each a study in precision.

The fire in the water we are hunting is bioluminescence, less of a burn than a dazzle of cold blue-green light. Although this happens in the night seas worldwide, it’s more realized in some places than others. In Puerto Rico, Phosphorescent Bay is named for the phenomenon. In the Galapagos, I've dived into Tagus Cove late at night and the bio-light there consumed me, exploding with each exhalation. On the beaches of the Outer Banks of North Carolina, I've seen puddles of it abandoned on the sand by the ebb of tide. I guess it’s been taking place in this particular lagoon for thousands of years, but we’ve only recently caught on.

Guides will take people to such places, but I usually like to go it alone, or with a few good friends. The risks may be a bit greater, but the surprises always seem somehow more real. I paddle out into the deeper canal and the surface around me becomes suspiciously flat, as if something immense is moving just below. My little boat wobbles gently. Within seconds, the back of a manatee materializes a few feet away, its gray, barnacled body like a gigantic sausage.

A shaggy snout gently breaks the water, human-like eyes deeply set, each inside a starburst of wrinkles. It glances at me, inhales. From inside its massive body, the air resonates as if in a cave. Then it sinks back down. I look over at Michelle, smiling broadly, without guile.

Despite its size, the coming and going of such an animal was incredibly delicate, almost like a disassembling of molecules. It could have flipped me in a heartbeat if it had wanted. I am exhilarated, and also deeply thankful I am still upright.

We paddle north where the canal meets the Mosquito Lagoon. It is twilight and the primitive landscape is golden. Men are fishing and drinking beer on the shore, many of them fried after hours of it. A really bad country music song celebrating the glories of "redneck women" blares from a pick-up truck. There is a small mangrove island offshore and we paddle towards it, riding a gentle evening breeze. As we go, the gray dorsals of a pod of bottlenose dolphins slice through the water nearby.

The sun vanishes and a dark cloud bank on the horizon begins to shoot out jagged spires of lightening, soundlessly. I look back to the land, now a half mile away, and see most of the fishermen packing to leave. The music shuts off and what remains is the slosh of our hulls, the cry of wading birds, the muffled sighs of anticipation.

The lagoon is encircled by public land; like the manatee, it’s a relic of what used to be. The landscape here was protected decades ago when the government bought a massive swatch of coastline to buffer its rocket launching at the Kennedy Space Center. In a strange twist, the ambitions of the future have preserved the past. Bobby, a cardiologist by day, sometimes brings his flats boat here to fish for sea trout and reds that school over the sea grasses and sandy shoals of the shallow, clear lagoon.

The cold light remains hidden and I find myself wondering if it will actually turn on tonight at all. We have brought Cyclamen sticks and we individually snap the plastic tubes to make them glow and hang them around our necks to keep track of each other. This seems a simple task, but I botch it and, for the moment, the lanyard tightens on my forehead, the glow-stick hanging against my nose, and I can't help but smile. A few of the others laugh good-naturedly at this. These are people who cherish the immediacy and enchantment of this moment, and I am glad to be here with them.

We float in the lagoon, letting the gentle evening breeze push us. It is almost completely dark now. We are all silhouettes with light sticks, finer details lost to the night. Suddenly I hear Alex’s voice from somewhere nearby, as if announcing the arrival of a special guest, one syllable at a time: “It’s hap-pen-ing.”

I look over to where I know Michelle to be. As she moves her paddle through the water, it glows dim with turquoise and she lets out a long, low woooow. I turn in my seat, watching as my own blade draws up the cold light. I hear murmurs rise around me, voices slightly higher and full of wonder, and I realize everyone is doing a version of the same thing, creating light from water. The alchemy has taken time to cook, but now it has us in its grip.

We paddle back toward the canal, where marine life is more concentrated. The lagoon water under us is so clear we can see through it, can watch as the grasses on the bottom glow with the light. Small fish and then larger ones, down deep, are outlined in blue-green.

Once we are in the canal, sunken logs on the bottom effervesce with color. Suddenly, the form of a massive alligator swims under us, odd, tiny arms from its body swishing the blue. It’s amazingly graceful, and, like the wading birds, its movements are precise.

Crabs drift along, glowing, sometimes bumping into my hull, hard calcium shells clanking oddly against plastic. Alex cups her hand in the water, and the liquid she holds sparkles as if electrified. In the distance, a dolphin arches out of the water, bringing a massive column of light with it.

I know, intellectually, that tiny, single-celled plankton called dinoflagellates do this, absorbing energy from the sun and releasing it to confuse predators at night, twisting and turning in the water. But that doesn’t explain the full magic of it to my senses. Another cove splays from the canal and we paddle into it. It is shallow and populated with great schools of mullet. When Bobby and others move far ahead they spook the mullet and the fish begin to leap from the water in great explosions of energy, like low-level skyrockets. Sometimes, in their jumps they whack into our boats; sometimes, into us. I look down, see a blue-green stingray move next to my hull, its wings undulating as if it is flying in the water.

Above, stars have filled the void over the cloud banks, and now a meteor traces a line through them. A collective murmur rises at once from us, an exhalation of natural awe. It seems as if the sky has split in two, no clear line left any more between it and the water around us. And now we have stopped being writers and doctors and whatever else we are and have become kids, alive only for this moment, in this place

.

I drift some more and it vaguely occurs to me that stardust started it all, showering this earth with its energy so long ago, and now, many molecules later, here we are in a dark Florida lagoon, watching it happen all over again. Like the dinoflagellates, we twist and turn in the night, glowing blue-green ourselves, a theater of creation in the mangroves.

We are all quiet now, and, soaked with the energy of the stars, as fully conversant as we will ever be.

"Rediscovering Rawlings, a River and Time"

A colorful immersion in the experience of filming and considering nature and literature in modern Florida

Losing It All To Sprawl: How Progress Ate My Cracker Landscape

Named one of the "Best Books of 2006" by the national Library Journal.

ANOTHER HABITAT in the biologically diverse Wekiva-Ocala Corridor. This is a pine flatwoods in the Lower Wekiva River State Preserve. My sojourns to natural places like this help provide some balance to the otherwise chaotic experience of being afflicted by rampaging, poorly executed development, otherwise known as sprawl.

Sunken Cities, Sacred Cenotes and Golden Sharks:

Travels of a Water-Bound Adventurer (University of Georgia Press. Spring 2004)

Bill Belleville's "Sunken Cities, Sacred Cenotes and Golden Sharks" is an engaging collection of essays and creative non-fiction stories in which the author travels the backwaters of Florida, the Caribbean and Latin America in pursuit of adventure and discovery. His introduction explains his lifelong connection with water, revealed in his memories of growing up on a peninsula. As an adult, he quests for ways in which the aquatic world shapes local cultures and defines a 'sense of place.'

In the upper Amazon, he searches for the Boto, the mythological freshwater dolphin. Later, in the lower Amazon, Belleville journeys into the heart of Guyana to explore the primal "Lost World" jungle landscape. His adventures take him to the once-prosperous 17th century pirate city of Port Royal, Jamaica---now under 30 feet of water. In the Dominican Republic, he joins archaeologists as they excavate rare pre-Columbian Taino artifacts from the dark depths of a sacred cenote.

Adventure leads him to the Galapagos Islands where he follows in Charles Darwin's footsteps in the "cradle of evolution." He joins native fishermen in Trinidad on a hunt for the rare golden hammerhead shark. In Cuba, he dives off the isolated southern coast at night in search of the illusive flashlight fish. In the Turks and Caicos, he tries to figure out why queen conch are so cherished that they are included on that country's national seal.

WHAT PEOPLE ARE SAYING:

• "This collection of essays brings the reader to places that are noted for archaeological treasures, rare plants and animals or great scenery, and water if the common denominator. Belleville, travel writer, scuba diver, and boater, seems always to be wet or preparing to be wet. As his armchair cmpansions, readers may stay dry, but the expressive and descriptive proses allows them to experience the discovery and excitement as if they were there themselves. In the Amazon, the quest is for a freshwater dolphin. In the Florida Keys, it's the quiet backwaters that preserve the past, and so on around the globe. Belleville is an old fashioned adventurer, excited by what he finds, seeking just for the joy of finding. He must also be a man of great charm as he seems able to coax the most arcane information from his local guides....As a book to read at leisure, it is a fine treat."

-- Danise Hoover, Booklist

• "I admire the precision, the poignancy and the passion of Bill Belleville's prose."

--Don George, Lonely Planet Global Travel Editor

• "What splendid adventures Bill Belleville guides us through! He is one of our great modern explorers, questing for gods in a time of technology, lusting for life. Here in this sensuous and unforgettable book he navigates us as deftly through language as he does Amazonian rivers or limestone fountains deep within the earth. His journey narratives are fluid, fresh, and piercingly poetic; what he finds is ceaselessly fascinating. I would travel with Bill Belleville to the ends of the earth."

--Janisse Ray, author of 'Wild Card Quilt: Taking a Chance on Home' & 'Ecology of a Cracker Childhood'.

• "Bill Belleville's writing is like a stream of phosphorescence in the ocean that he loves so well. Belleville's language creates a dreamy double vision, blending archetype and precision so well that the reader is convinced he has not merely read about jeweled morays and pink dolphins, but floated alongside them in tropical waters. These tales are not hairy-chested, macho attempts to conquer snowcapped peaks, but adventures into sensuality and meaning."

--Susan Zakin, author of 'Coyotes and Town Dogs: Earth First! and the Environmental Movement'

• Environmental writer and filmmaker Bill Belleville's not content to be at the water's edge, idly senescent in sea breezes and salt air. Instead, he's driven to cross over the edge and into the sea to dive in its depths and become a part of the hidden universe.

It's a world that, like the mythological sirens, has called him since he was a 7-year-old, looking wide-eyed through his first swim mask in a pool in Sarasota, Florida, and peering through the glass bottom of a tourist boat in Silver Springs as bass, mullet, and bluegill darted above a solid, still alligator.

'One day, I promised myself, I would learn more about this other reality,' Belleville says. 'Someday, I would have adventures and they would take me across the water and under it.'

Those adventures have taken the Maryland native across the world to desolate undersea places, to watery graveyards, sunken wrecks and treasures and human bones left behind in a mysterious cenote to appease old gods.

A resident of Sanford, Florida, Belleville has helped produce documentaries for Discovery Channel Online and written several books and articles in a style that is poetic, down-home and scholarly.

His latest work, "Sunken Cities, Sacred Cenotes and Golden Sharks," published this spring, is a collection of true tales of his travels that seamlessly weaves history, archaeology, ecology and some heart-pounding terrors and triumphs in the deep. Through his recollections and empathy for what was, he stirs up old souls amid the silt.

For example, Belleville descends five stories into a sacred cenote---a deep limestone sinkhole---in a Dominican Republic jungle, and then into a pool of water as its based where ancient Taino people tossed sacrifices. Heart thumping, a nitrogen buzz setting in from his breathing apparatus, he fins past a natural shelf and discovers prehistoric and human bones that scientists missed. He apologizes to the Taino gods for his trespass.

In Guyana, he finds he way through the Iwokrama rain forest preserve, hears monkey screams and travels upriver with a rum-soaked crew, motoring past brilliant macaws and green parakeets. The author also drifts in scuba gear over the 300-year-old sunken city of Port Royal in Jamaica while he wonders about the souls lost in the 1692 earthquake and the bones of children found beneath a toppled wall.

On the Suwannee River in Florida, he explores some of the river basin's 200 springs "traveling into the cellar of Florida," and sets up night camp on a sandbar, catching three pairs of red eyes glinting in the path of his flashlight beam.

Both a dauntless and fearless wet-suited explorer, Belleville swims thoughtfully into primitive time and shares them with us."

-- Susan P. Respess. "Coastal Cruising" magazine. May/June 2004

In the upper Amazon, he searches for the Boto, the mythological freshwater dolphin. Later, in the lower Amazon, Belleville journeys into the heart of Guyana to explore the primal "Lost World" jungle landscape. His adventures take him to the once-prosperous 17th century pirate city of Port Royal, Jamaica---now under 30 feet of water. In the Dominican Republic, he joins archaeologists as they excavate rare pre-Columbian Taino artifacts from the dark depths of a sacred cenote.

Adventure leads him to the Galapagos Islands where he follows in Charles Darwin's footsteps in the "cradle of evolution." He joins native fishermen in Trinidad on a hunt for the rare golden hammerhead shark. In Cuba, he dives off the isolated southern coast at night in search of the illusive flashlight fish. In the Turks and Caicos, he tries to figure out why queen conch are so cherished that they are included on that country's national seal.

WHAT PEOPLE ARE SAYING:

• "This collection of essays brings the reader to places that are noted for archaeological treasures, rare plants and animals or great scenery, and water if the common denominator. Belleville, travel writer, scuba diver, and boater, seems always to be wet or preparing to be wet. As his armchair cmpansions, readers may stay dry, but the expressive and descriptive proses allows them to experience the discovery and excitement as if they were there themselves. In the Amazon, the quest is for a freshwater dolphin. In the Florida Keys, it's the quiet backwaters that preserve the past, and so on around the globe. Belleville is an old fashioned adventurer, excited by what he finds, seeking just for the joy of finding. He must also be a man of great charm as he seems able to coax the most arcane information from his local guides....As a book to read at leisure, it is a fine treat."

-- Danise Hoover, Booklist

• "I admire the precision, the poignancy and the passion of Bill Belleville's prose."

--Don George, Lonely Planet Global Travel Editor

• "What splendid adventures Bill Belleville guides us through! He is one of our great modern explorers, questing for gods in a time of technology, lusting for life. Here in this sensuous and unforgettable book he navigates us as deftly through language as he does Amazonian rivers or limestone fountains deep within the earth. His journey narratives are fluid, fresh, and piercingly poetic; what he finds is ceaselessly fascinating. I would travel with Bill Belleville to the ends of the earth."

--Janisse Ray, author of 'Wild Card Quilt: Taking a Chance on Home' & 'Ecology of a Cracker Childhood'.

• "Bill Belleville's writing is like a stream of phosphorescence in the ocean that he loves so well. Belleville's language creates a dreamy double vision, blending archetype and precision so well that the reader is convinced he has not merely read about jeweled morays and pink dolphins, but floated alongside them in tropical waters. These tales are not hairy-chested, macho attempts to conquer snowcapped peaks, but adventures into sensuality and meaning."

--Susan Zakin, author of 'Coyotes and Town Dogs: Earth First! and the Environmental Movement'

• Environmental writer and filmmaker Bill Belleville's not content to be at the water's edge, idly senescent in sea breezes and salt air. Instead, he's driven to cross over the edge and into the sea to dive in its depths and become a part of the hidden universe.

It's a world that, like the mythological sirens, has called him since he was a 7-year-old, looking wide-eyed through his first swim mask in a pool in Sarasota, Florida, and peering through the glass bottom of a tourist boat in Silver Springs as bass, mullet, and bluegill darted above a solid, still alligator.

'One day, I promised myself, I would learn more about this other reality,' Belleville says. 'Someday, I would have adventures and they would take me across the water and under it.'

Those adventures have taken the Maryland native across the world to desolate undersea places, to watery graveyards, sunken wrecks and treasures and human bones left behind in a mysterious cenote to appease old gods.

A resident of Sanford, Florida, Belleville has helped produce documentaries for Discovery Channel Online and written several books and articles in a style that is poetic, down-home and scholarly.

His latest work, "Sunken Cities, Sacred Cenotes and Golden Sharks," published this spring, is a collection of true tales of his travels that seamlessly weaves history, archaeology, ecology and some heart-pounding terrors and triumphs in the deep. Through his recollections and empathy for what was, he stirs up old souls amid the silt.

For example, Belleville descends five stories into a sacred cenote---a deep limestone sinkhole---in a Dominican Republic jungle, and then into a pool of water as its based where ancient Taino people tossed sacrifices. Heart thumping, a nitrogen buzz setting in from his breathing apparatus, he fins past a natural shelf and discovers prehistoric and human bones that scientists missed. He apologizes to the Taino gods for his trespass.

In Guyana, he finds he way through the Iwokrama rain forest preserve, hears monkey screams and travels upriver with a rum-soaked crew, motoring past brilliant macaws and green parakeets. The author also drifts in scuba gear over the 300-year-old sunken city of Port Royal in Jamaica while he wonders about the souls lost in the 1692 earthquake and the bones of children found beneath a toppled wall.

On the Suwannee River in Florida, he explores some of the river basin's 200 springs "traveling into the cellar of Florida," and sets up night camp on a sandbar, catching three pairs of red eyes glinting in the path of his flashlight beam.

Both a dauntless and fearless wet-suited explorer, Belleville swims thoughtfully into primitive time and shares them with us."

-- Susan P. Respess. "Coastal Cruising" magazine. May/June 2004

THIS IS THE BUTTRESSED STUMP of a bald cypress tree that was over 2,000 years old when cut. I'm in a remote dry swamp that's part of the Wekiva-Ocala Corridor in Lake County, surrounded by the remains of trees logged here 75 to 100 years ago. (Check out the water mark on the trunks from when the bottomland was in flood.) There was no trail here, just a narrow animal path that, as we descended into the dry swamp, dissolved. We saw fresh black bear tracks and almost-ripe wild blueberries and, in the creek, a dead deer. I was cheered that new cypress, like the one in the left of the photo, are thriving here. This is a wild swatch of relic Florida landscape that has kept its quiet, and I am thankful for that. (Photo: Steve Phelan; June 2007).

"Deep Cuba: The Inside Story of an American Oceanographic Expedition" (2002)

"A fascinating dive into two worlds: the undersea kaleidoscope where mysterious creatures make their home, and the politics and culture of a scientific expedition. Bill Belleville is an astute observer and a great companion..." - Jan DeBlieu, winner of the Burroughs Medal for Nature Writing for "Wind"

"'Deep Cuba' makes an eloquent argument for deep sea diving, scientific inquiry and ending the embargo. I learned something new on every page." - Tom Miller, author of 'Trading With The Enemy: A Yankee Travels Through Castro's Cuba"

"Engaging...Environmental writer and diver Bill Belleville works hard to achive a documentary-maker's dream: Exciting a broad public empath for a place and its creatues." - Kirkus

"Above all, I apreciated (Belleville's) thoughtful, informative and even poetic account...Belleville is an articulate and skilled advocate and we should all pay attention to what he says..." - Solares Hill

"This is the good stuff: An expansive and wide ranging journal by a keen-eyed observer of nature, politics and people..." - Tom Lassiter, The Orlando Sentinel

"Through his prose, Belleville artfully blends dramatic human tension in what could have been a drab account of scientific specimen collection...He is a great story teller." - Key West Citizen

"'Deep Cuba' makes an eloquent argument for deep sea diving, scientific inquiry and ending the embargo. I learned something new on every page." - Tom Miller, author of 'Trading With The Enemy: A Yankee Travels Through Castro's Cuba"

"Engaging...Environmental writer and diver Bill Belleville works hard to achive a documentary-maker's dream: Exciting a broad public empath for a place and its creatues." - Kirkus

"Above all, I apreciated (Belleville's) thoughtful, informative and even poetic account...Belleville is an articulate and skilled advocate and we should all pay attention to what he says..." - Solares Hill

"This is the good stuff: An expansive and wide ranging journal by a keen-eyed observer of nature, politics and people..." - Tom Lassiter, The Orlando Sentinel

"Through his prose, Belleville artfully blends dramatic human tension in what could have been a drab account of scientific specimen collection...He is a great story teller." - Key West Citizen

"River of Lakes: A Journey on Florida's St. Johns River." (2000)

"Belleville reveals the waterway's exotic voluptuousness...in writing that is both silvery and refreshingly unrehearshed...two qualities much in keeping with the mileu. Belleville creates in the reader a protective affection for the St. Johns..." - Kirkus

"A tour-de-force..." - Publishers Weekly

"Every once in a while, a book comes along that explores and defines a place or a time so thoroughly, holding up for view what otherwise is transient and hidden, that it can be called a classic. Such a book is 'River of Lakes,' a natural and cultural history reminiscent of Thoreau's 'Walden' or William Warner's 'Beautiful Swimmers'...Belleville's writing is by turns lyrical, elegiac, scholarly, down-home, and downright hilarious..." - Florida Today

"[Belleville] establishes his kinship with William Bartram...and other artists who hvae felt the tug of the river's currents." - Audubon magazine

"Eloquently captures one man's quest to explore both the known and unknown about a mesmerizing body of water." - Southern Living

"A superb book." - The Tampa Tribune

"Belleville's keen insight, deep research and sparkling prose carry us down Florida's longest river and we are better for the trip." - Tallahassee Democrat

"Filmmaker Bill Belleville has written a fine account of the St. Johns...a definitive book." - The Miami Herald

"River of Lakes is one riveting read. Belleville, a resident of Sanford, Fla., is a writer and filmmaker whose cause is ecology. He's well tutored in botany, history, anthropology, archaeology---just about any 'ology' there is. Belleville's words stir thought. The St. Johns looks different to me now." - Daytona Beach News-Journal

"Bill Belleville has written a wise and inspired book that enriches the artistic legacy already inspired by Florida's St. Johns River...This is an important and beautifully written work that deserves to be widely read as a lesson in learning to know and love the damaged places that surround us." - Alison Hawthorne Deming, poet & essayist, "Monarchs", "Temporary Homelands."

"A thoughtful and engaging book about a great American river. [Belleville] fully appreciates the natural values and rich history of the St. Johns and makes what I hope is a compelling case for the preservation of what is left of its native ecology and wild spirit" - Christopher Camuto, author, "Another Country: Journeying Towards the Cherokee Mountains

"A tour-de-force..." - Publishers Weekly

"Every once in a while, a book comes along that explores and defines a place or a time so thoroughly, holding up for view what otherwise is transient and hidden, that it can be called a classic. Such a book is 'River of Lakes,' a natural and cultural history reminiscent of Thoreau's 'Walden' or William Warner's 'Beautiful Swimmers'...Belleville's writing is by turns lyrical, elegiac, scholarly, down-home, and downright hilarious..." - Florida Today

"[Belleville] establishes his kinship with William Bartram...and other artists who hvae felt the tug of the river's currents." - Audubon magazine

"Eloquently captures one man's quest to explore both the known and unknown about a mesmerizing body of water." - Southern Living

"A superb book." - The Tampa Tribune

"Belleville's keen insight, deep research and sparkling prose carry us down Florida's longest river and we are better for the trip." - Tallahassee Democrat

"Filmmaker Bill Belleville has written a fine account of the St. Johns...a definitive book." - The Miami Herald

"River of Lakes is one riveting read. Belleville, a resident of Sanford, Fla., is a writer and filmmaker whose cause is ecology. He's well tutored in botany, history, anthropology, archaeology---just about any 'ology' there is. Belleville's words stir thought. The St. Johns looks different to me now." - Daytona Beach News-Journal

"Bill Belleville has written a wise and inspired book that enriches the artistic legacy already inspired by Florida's St. Johns River...This is an important and beautifully written work that deserves to be widely read as a lesson in learning to know and love the damaged places that surround us." - Alison Hawthorne Deming, poet & essayist, "Monarchs", "Temporary Homelands."

"A thoughtful and engaging book about a great American river. [Belleville] fully appreciates the natural values and rich history of the St. Johns and makes what I hope is a compelling case for the preservation of what is left of its native ecology and wild spirit" - Christopher Camuto, author, "Another Country: Journeying Towards the Cherokee Mountains